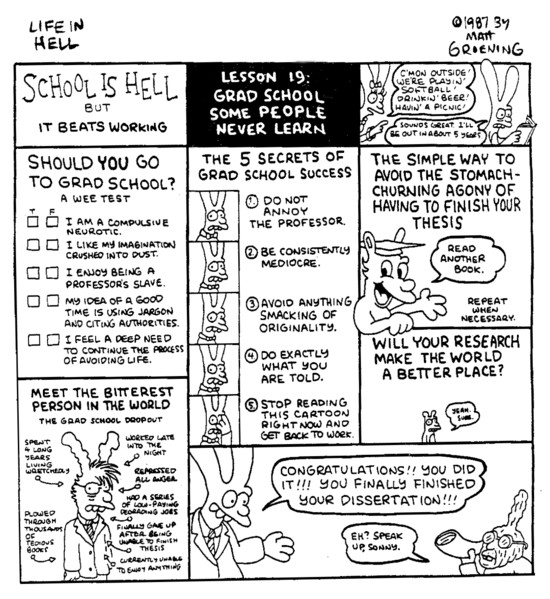

I spent four years in graduate school at large state universities. Toward the end of that time, someone posted this Matt Groening “Life In Hell” cartoon on the bulletin board. (For youngsters out there, bulletin boards were a primitive read/write social media structure, made from tree-bark, to which humans once attached sheets of paper using tiny steel pins. Think of them as two square meters of non-hyperlinked anonymous Facebook.)

I had no idea who Matt Groening was at the time. (The Simpsons were still in their early lives on The Tracy Ullman Show.) But the comic struck a chord with me as it did with so many of my fellow students. Check out the miserable chap in the lower left panel. He probably had an experience like this real-life example: Halfway through my last year of graduate school, a faculty member suddenly departed for a job in private industry on another continent, promising to return after his sabbatical. He didn’t. His students had to find new advisors and start over. I don’t know how many of them gave up.

But this isn’t about Grad School Gone Wrong. This is about the phrase that originally caught my attention: “…the stomach-churning agony of having to finish your thesis.” Writing was never stomach-churning agony for me. It’s difficult and time-consuming, but it was never stomach-churning. Here’s a little story about that:

When I was working on my Master’s degree in 1984-1986, there were two paths to graduation. Students could choose between writing a Thesis or taking a series of Comprehensive Examinations (“Comps” for short). I was a small-town 25-year-old, new to grad school, and terrified of Enormous State University academic politics, so I listened carefully to what the more experienced students were saying about the process. The general consensus was that the Comps were a nightmare. Students had to pass three Comps in three different specialties of computer science. The tests changed each year, and some students said that if Professor X wrote the Comp for Specialty Y, you had to take his class in it to have any hope of passing. And no one had a kind word for the grading process. Like any science exam, the questions generally had one correct answer. A student might get partial credit for a partially solved problem, but “partial” is nearly impossible to quantify objectively. If the grader knew the student, they might differentiate between minor misunderstandings and outright incompetence, but that also led to claims of favoritism.

On the other hand, to go the Thesis route, students had to find an advisor (on their own), do some work for that advisor (for course credit!), write up the work (for more course credit!), and get three faculty members into a room for a one-hour presentation called the Thesis Defense. The last step was often feared, but if the student was well-prepared, the defense was largely a formality. Mind you, “well-prepared” included being kind to secretaries and selecting faculty members who didn’t hate the advisor, but that wasn’t hard to figure out. Despite the apparent simplicity of the Thesis route, the student consensus was to go with the Comps. They said, “I can’t face the idea of writing a paper that big.”

Really, I thought? Is writing a single 100-page paper truly the unclimbable greased pole? Did they not understand their own complaints about the Comps–that the exams were, in fact, three greased poles of unknown height? Thirty-five years later, I still don’t understand their perspective, but I can at least accept that they honestly felt that way. (When I was 25, I just thought they were idiots.)

Back then, I couldn’t articulate the difference between the Thesis and Comps as well as I can now, but even then I sensed it intuitively. The prevailing mythology asserted that the Thesis was subjective and the Comps were objective, but that simply wasn’t true. Even a cursory examination revealed that the Comps were plagued with subjective choices. The fundamental difference was not in the question of objectivity or subjectivity, but in the availability of feedback to the student. Students taking a Comp got no feedback until after the test was graded, and by then it was too late to do anything but beg for partial credit. Students writing a Thesis got feedback at every stage of the process, which gave them plenty of chances to fix everything before the Thesis Defense.

So, as you might guess, I took the easy road and wrote a Thesis. It wasn’t great science (very few Masters Theses are), but I was able to achieve in two years something that took other students three or four years, just because I wasn’t afraid to write a paper.